Sunday, May 31, 2009

FOUND

I found a picture of you, the girl I once loved, changed time just to be with. The girl I slowed down to meet, sped up to miss. There’s a ring on your finger, but this is not what I notice. What I notice first is your confidence. Not caring that a camera has just collected you up into eternity, added you to that growing landfill of available information. Your details are teeth, thin wrists and a red string bracelet. You laugh, truly unaware of the consequence this laugh will have.

FIXTURES

I got a job as a bus driver for a regional women’s basketball team, driving them around through small country towns, dropping them at school halls, buildings sided with corrugated iron, even sometimes bitumen outdoor courts. I’d stand around outside, smoking, while they played their games, chatting to the other coach drivers, all men, all just as alone as me. It wasn’t a sexual thing, they all assured me. It wasn’t for the power, they said. One showed me an old mattress in his cargo hold. Another had a set of bath oils in his glove compartment. All had Kenny Loggins tapes stuck in the deck. The love of the game, they told me. Competition.

VICINITY

Just to have you there. That was all I ever wanted. That gentle pluck of breath as your lips unstuck, the sounds of you moving without knowing.

GREENSLEEVES

When I got to old to care, I’d chase the ice-cream trucks that came down my street because they drove so slowly, and sometimes they’d throw a wonky soft serve at me, which, flying through the air, missing me by metres, was about the funniest thing I’d seen in my whole life.

ANCHORS

After it happened, I went out onto a ship and stayed there. Packed what I owned and walked up the gangplank. Hauled it up behind me leaving only air. A steam-powered life, all that power at the mercy of a current. Stayed in the bilges, making anchors. Making them heavier and heavier, making more and more, until there was no room left, until I felt the soft thump of the sea floor.

CRIME

He came to me with an idea. Arrived at the coffee shop with a blueprint rolled under his arm, a torch in his mouth. I told him to take off his eye-mask, but he wouldn’t. Said his skin was so dry he had to leave it on. He unburdened himself of his grappling hook, clanged it on the table, upset my latte. He was so excited I could see little patches of sweat forming on his skivvy. This is it, he told me, holding up a Hessian sack with a dollar sign painted on it. I took a sip of my coffee, and waited.

CUSTOMERS

I thought the Admiral’s hat looked good, but you’d already left the shop. We’d been tailing each other in and out of boutiques all morning, summing up our dwindling feelings with shakes of the head, exhalations of air. I gave the hat back to the shop assistant, apologised in my own thin way. I found you outside, sitting at a café table, ignoring the waiter hovering at your shoulder. Something in your eyes always scared away customer service. I sat down in the opposite seat. So where now, I asked. The first words I’d spoken all morning. Nowhere, was your reply. Just nowhere.

DISCOVERY

When I got to work, it was all anyone could talk about. That picture of the bearded guy—the scientist, we supposed—walking out of the Borneo forest, cradling it like a baby. The thing, whatever it was, looked a little bit like a cat, but hairless. Those green piercing eyes, that foot-long neck. Do you think it’s really a dinosaur, said one woman. Not a real one, said someone else, it’s like a—a—descendent or something. How did it survive, said our boss, who’d come over to join the conversation. I guess it just kept its head down, I said, and this proved to be sufficiently funny to elicit stooping-head dinosaur impressions from my co-workers for the rest of the day. Then the rest of the week. When they were still doing it after a year, I had to ask them to stop. But by that time, of course, they’d all done such permanent damage to their backs that they couldn’t stop, even if they’d wanted to.

DEPARTED

At the séance, there was another couple who had lost a child. They were older than us, parental-looking, I guess. The wife had on a long red ribbon, tied into her hair and let fall all the way to the backs of her knees. I asked her if the ribbon was a special sign, and she simply started crying. We took our places at the table, each couple side by side. You never let go of my hand. Even as the medium asked us to stand and move around the room, even as the husband from the other couple began to shout animal sounds, even as the temperature dropped and grief cracked at the edges of our eyes—even then, you held my hand, tight, as if to let go would be to lose that last part of us.

CELEBRATE

For my birthday, I set up a blue screen in my lounge room. I wanted memories of my life projecting on the screen, me sitting in the foreground. Me, the age I am now, seemingly sitting with my younger selves. Talking to them, advising them, laughing at their follies and nodding with their mistakes. Smiling at their achievements, clapping at their proudest moments. Then taking a large knife from the kitchen and slashing the blue screen down, tearing to ribbons my face at all its ages, destroying the memories, the anniversaries, the milestones, every last one. I really hate my birthday.

FRICTIONLESS

In the midst of the music, I sidled up to her. She had entranced me all evening. That green dress, those slender tense arms. I signalled the bar for a gin fizz, leant back against the marble, feeling her subtle heat at my arm, taking in a cool view of the room. I’ve taken the liberty, I said, of ordering you a drink. She looked over slowly, as if to process every part of me. A chill ran up my arms. Oh you don’t want to get to know me, she said. I’m frictionless. Her voice was like filtered air. I said, Let me be the judge of that. The gin fizz arrived, and I pushed it towards her, with one finger, leaving a faint trail of condensation on the bar. Trust me, she cooed, moving her body away from the drink. Frictionless, I said. I think I can handle that. I spun my torso with practiced ease. I’m pretty light on my feet myself. She raised a single eyebrow. Alright, she said. Kiss me then. I coughed slightly. Pardon? Kiss me, she said again, turning back. If you can kiss me I’ll take you home. Never being one to back down from a challenge, I leant in towards her, cupping a palm against her cheek. Suddenly, my arm had shot out behind her head. I moved in again, with the same result. Perturbed, and slightly embarrassed, I tried to grab her face with both hands and kiss her full on the lips. The last thing I remember is the taste of cherry, and the horrific sound of my teeth hitting the tiled floor.

BABY

When he came out, or at least when he appeared first in my memory, he was a beautiful, broken thing. He was ours, somehow, this barely-grown chromosome. No body yet, just a shape. And you, next to him: the puzzle with that one last piece beside you.

HUMPS

It was maybe because she watched so much tennis that she was obsessed with grading things. She had a favourite player, a short angry guy who was prone to outbursts of both brilliance and ineptitude, and therefore prone to sudden jumps and lapses in world rankings. She gave everything a status relative to everything else. If you were unfortunate enough to ask her how she was going that day, rather than just saying good or fine, like every other human would when asked this question, she would have to place the day in a rank among all the others she had experienced. She kept journals, lists, meticulously evolving observations that placed everything she came across in immediate relation to other similar items and experiences. It really did get too much sometimes. One day, fed up, I asked her what her favourite thing in the world was. She looked at me blankly, pulled out her newest journal, and started writing.

CUT

I used to live in a tiny flat above a barber’s shop. The rent was cheap and it was close to my job, but the only way to get to my flat was through the salon. No matter what time of day, the cast never seemed to change: three old men lying back in the barber’s chairs, the barber moving slowly between all three. I’d stop and watch sometimes, when I had nowhere to be particularly quickly, and I’d shoot the breeze with the barber and his clients, letting them complain at me about sport and politics, and I’d lean on the magazine rack and agree. Eventually, the smell of old aftershave and beard clippings became more of a home than my home. I liked the old guys, their faded faces in the mirrors, the predictability of it all. Soon I stopped leaning on the magazine rack and took out a broom. Then I started washing the razors, dipping them in the old tub of disinfectant, sitting on the barber’s stool, drying the blades with an old soft cloth. It just felt right, I guess, when the barber finally handed me a pair of scissors, made a circling motion with his hands.

LOST

You came home bleeding. Stuttered through the door with ballerina feet, falling into that little table in the hall. I ran from the study, hearing the crash, finding you face down the floorboards. Shaking you into consciousness, brain screaming fear, arms shaking. That rash all down your twitching face, raw meat red, hot to the touch. What’s wrong what’s wrong what’s wrong. Water from the flower vase, blood between your legs. That precious bump that was your stomach, that swelling, that stupid stupid bruise.

ADAPTING

They were making a movie version of my favourite book, so I went down to where they were filming it. At the entrance to the studio, I showed my copy of the book to the security guard, and he waved me through. I had some strong ideas on how this movie should be made. I had an awful feeling they were going to try and change the setting, and sure enough, when I walked up to the set, I saw that Victorian England had been changed to a West Coast American high school. The two main characters, a cobbler and a midwife respectively, had been turned into a quarterback and a cheerleader. Their emotional journey of love and redemption had also transmuted—now the themes seemed mainly to be getting laid and partying down. I stormed up to the director and demanded an explanation. I waved my dog-eared copy of the book in his face, explained how much it meant to me, how these simple dots of ink on bound paper had changed my life, how this cinematic monstrosity would ruin it forever. He stood, and listened intently to me, as around him production stopped. The actors and the stage hands and the assistants were all silent, listening to what I had to say. When the director offered me a walk-on part, I was so elated that I dropped the book on the stage floor and forgot about it. I didn’t worry though. When I was famous, I’d buy another.

HUMPS

He came up to me on the street, this kid, all dirty and yellow-eyed and obviously sick. I took time to stop because he was so obviously in need of help, setting him apart from the usual array of panhandlers I encountered day-to-day. What caught my eye most, though, was his silk shirt. Not a normal silk shirt, but patterned, broken up into primary coloured squares like a board game. He grabbed onto my coat, hanging his weight off my lapels. It was only after I saw his feet—shod in soft leather calf-length boots—dangling a few inches off the ground, that I realised how little bodyweight he had. Please, he said with a tiny, scratchy voice. Please. Then he coughed out a cloud of what I could only assume was dust. They made me race, he said. So many races. I put him down on the ground, patted his back, made him cough until all the dust had been expelled from his lungs. I asked him very slowly and deliberately whether he was an escaped camel jockey and when he nodded I thought back to the public safety campaign. There was a rhyme, wasn’t there? A slogan we all had to remember. A number we had to call.

GHOST

We moved into the house when you were four months pregnant, which somehow made it even more like a horror movie. All those stairs to the front door, your arms pressed to your kidneys, no electricity. Eating baked beans from the tin like bomb-shelter huddlers, white sheets draping, banshee winds. Real estate tales swooping inside our heads: Going for a song, Making a killing, Renovator’s dream. Apples for desert, red paint waiting in tins: gender neutral for his or her nursery. Nothing but our breathing. Echoes. Breathing.

EFFIGY

I was slightly blackmailed into attendance, seeing as I’d kicked his dog. Not deliberately, but enough to maybe bruise a rib. So there I was. The rally. Rallying against—well, it seemed to me—whatever was going. Thousands of them: activists, I supposed. He made me hold a sign that promoted what was no doubt a powerful and damning acrostic, but one rendered nonsensical by his abysmal handwriting. Looking around me, I marvelled at the wasted time and talent that had gone into all the signs, costumes and general papier-mâché constructions. All this art in aid of what generally amounted to just shouting and stomping. Suddenly, a roar from the crowd, and a figure leapt above our heads: a crude scarecrow in a business suit, taffeta hair streaming from its pinched-pillow head. A chant rose up above the crowd’s hum—Burn, Burn, Burn—and the figure’s clothes shot through suddenly with flame, shocking me, inciting a shout from my own mouth—Burn, Burn, Burn—

THIRD

I woke up with three arms—in and of itself a strange thing, but not as strange as my third arm, which looked that much different to my other two that it had me very worried. Was it that the two arms I thought I had were that different to one another, or had a third, unrelated arm grown overnight? The third arm (let me call it that) was slender, brown and altogether more delicate than the other two. I attempted to flex its long pink-tipped fingers but all I managed was to move the fingers on my other two hands. Perhaps, I thought, I was dreaming. I used what was once my left hand (now first hand? Westernmost hand?) to pinch my new, third arm. I felt nothing, but heard a strange squealing sound behind me. Puzzled, I pinched again, and again the squeal, but louder, and a sudden force at my shoulders. Was it too early to phone the papers? Or television stations?

WORK

It happened so slowly that no one, least of all me, even realised. I’d been working on a particularly tough problem, chewing through printouts and drafts for nearly two days straight, subsisting on coffee and dark chocolate, hardly looking up to watch the sunlight appear in the sky and fall back down again. Eventually, I typed the last word, saved it, and stood up. My back had tightened like a piano string and I stretched it out. I was about to walk to the kitchen for a celebratory drink when I realised I couldn’t see the door. All around me was paper. Stacks of scrunched and folded documents, photocopies, pens, chocolate wrappers, even a broken pen, sitting atop a discarded reference book, ink spilt from its broken spine. All around me, a wall of my own detritus. I pushed through a drift of paper and found the door. I would clean it up later, I thought. For now, a stiff drink and definitely a nap. I opened the door, and more paper fell in. All through the house the same. A little panic grabbed my chest. Everywhere, paper, with my frantic scribblings scrawled across it. I peered out the window, and sure enough, a landscape of white.

A.M.

It was that fluorescent light that makes you bleary just thinking about it: a white-yellow flickering world where no one sleeps. I looked down at my hand where I’d written your words, in the half-dark, with a failing biro. Your late-night craving list. My skin flashed with strange white blotches, and I could hardly read the words. MIX, I made out, and ICE CREAM. Biscuit mix maybe. My mind was still back in bed, warm, covered-over bed: not here in this zombie market. It was two in the morning, and people still milled happily in the aisles. I wondered what their stories were. Shift workers? Millionaires? I held open the door to the ice cream fridge and stared until my eyes went numb. Above me, the upbeat fuzz of AM radio. And even I saw the irony of this frequency.

TRAPEEZE

She wanted to throw the fleas out, just kill them and destroy them. Even wanted to burn the towel. I gave her the cat, took the towel out to the backyard, saying I’d take care of it, like I was the manly, capable, impulsively chivalrous type. When in reality I turned left at the bins, opened the door to the shed. Pulled the sheet off a tiny bigtop tent. I stood for a moment, admiring the candy-stripes I’d painted laboriously by hand. I placed the towel down on the bench carefully, opened it up, scouring for acrobats, clowns, trapeze artists. And the ringmaster, who I knew would have a miniscule but massively impressive moustache.

POOL

I was learning to swim. A floating embarrassment that—at my age—I couldn’t stay alive in water. I chose the earliest possible class to avoid being shown up by four year-olds. The light was just a crack in the sky as I pulled up to the council pool for the first time. And yet, for some reason, I had slathered myself in sunscreen. I felt it inside my nostrils, felt the awkward drawstring pinch of swimwear. No one at the gates, just walked in across the freezing concrete. An old man with teak skin and pink swimming briefs stalked the bleachers. He waved when he saw me, jumped down the rows with a dancer’s surgical grace. My teacher, then, a portrait of aquaplaned age. He came up to stand right next to me. Nodded, pushed me in.

Saturday, May 30, 2009

OURS

We were sitting in a restaurant, overlooking the water, when you told me. Clasping my hand, looking down at your salad like it held all the answers. I said all those things people said in the movies, and you grinned with tears running into those creases at the corners of your mouth. It was funny how I’d looked at you before, but never really seen you. I wondered if your folded smile would be passed on into another life, or my nose, or your slow gentle way of blinking. I wondered if the world would still see the way I always tapped my foot, even after I was gone. Which parts of us would carry on, and which parts would end? Which echoes of our parents went on with us? I looked out to the water, my heart filling with waves, overlapping and overlapping until they inevitably met again.

BONSAI

Eventually, the whole town came out to see it. Why would you not? It was too small, too delicate, to even be photographed. All the papers carried were vague descriptions; newsreaders were reduced to incoherence without the shortcut of even a still image. I joined the long queue, the line that snaked from the museum right back through the city and out to the edge of the freeway. I passed people I hadn’t seen in years, nodded politely, exchanged theories as to what it would look like, once we got in to see it. I spent hours waiting, shuffling, waiting. Night came. I watched people leave the line in front of me, scattering like seeds in the wind, curiosity waning against hungry stomachs, unswept floors, unmissable television developments. Eventually I left too, tired, cold, irritable. There’d be a photo, somewhere, eventually.

CLOSING

I came into her shop just as she was flipping over the sign from OPEN to CLOSED. We made eye contact; her fingers flexed the plastic sign so it bowed in the middle, snapped back. She was sizing me up, I thought, trying to work out if I was worth staying open for. I raised my mouth into the sort of smile I make when I’m thinking too hard about smiling. She just stood there, and I watched her jaw muscles stretch and roll beneath her skin. The sign flipped, stayed, shook a little bit.

RATKING

I’d crawled down here, through the cramped spaces and tight turns, never able to lift my head above my shoulders. And for what—one chance at fame? I’d heard it on the radio, the news, this creature supposedly stalking our city from underneath. Sucking down toddlers through storm drains, clogging our pipes, shooting our shit right back into to our clean white bathrooms. A moratorium then, a citywide emergency. A Ratking. One chance to kill it. Room for one person to do it. And I’d had my share of heroics, caught the thrill of real life between my teeth and not wanted to let go. This would be, perhaps, my final high. Squeezing through tiny ventilation shafts above a city sewer, inch by painful inch, forever looking down through iron grates, waiting for that first view of a giant furred back, streaked with human blood. And a thousand eyes staring back into mine.

PAVEMENT

We were tired, bored, uptight, all that. What comes from walking too long in a single city, going up and back every single street, looking up and down every single building. We’d seen every sunrise from every window. We’d taken coffee in every single café and waited patiently at every single stop sign. Which was what surprised us about the drawing of the cavern on the pavement. On a normal pavement, where there had once been just grey concrete, spots of dried blackened gum, flecks of bitumen, was a chalk drawing of a cave, with walls disappearing down towards darkness. We looked at each other as if to say, should we? I felt your hand link into mine, and our knees tensed, each waiting for the other.

MIME

I was working as a mime in a run-down theatre restaurant when the magician came along. He had seasons, he said. Spent four weeks at a circus, another six on a cruise ship. The owners of the restaurant seemed very pleased to get him for a two-week appearance. They kept shaking his hand, slapping him on the back. I had my doubts. Who’s this clown, said the magician, actually turning around so he could stick his thumb back over his shoulder at me. He’s the mime, said the owners. The magician just spat out some air. Can a mime do this? He produced a live dove from inside his jacket and released it into the room. It flapped for a moment, gaining height towards the rafters. I mimed pulling out a shotgun, aiming, pulling the trigger. The dove seemed to freeze in midair, spun awkwardly, fell like a rock to the floor. A little puff of feathers wavered at the moment of impact. I raised the gun to my shoulder, squinted my eye, aimed it at the magician’s face. Bang, I said.

SPIKES

She worked for the railways, maybe. She’d come in wearing a reflective vest, with soot in her hair, with eyes wide and static like they’d been staring too long and too deep into dark tunnels. She’d have an orange juice, first, before anything else—a completely separate order. She’d sit on a high stool, at the ledge, at the window, nose pressed nearly to the glass. Whenever the milk frother was left in too long, whenever steam escaped from the coffee machine with a metallic hiss, her shoulders would hunch and she would begin to shake. We all wondered what it was she’d seen, what memories flashed through her mind.

KIDNEY

Of course, he ruined the day with his kidney in its little red bucket. He dragged it all the way down from his bedroom, moving with the deliberately clomping feet. The kidney was still fresh, relatively speaking, so at least the smell hadn’t kicked in yet. He had blood all down his front, which we didn’t ask about, as history had told us it was better not to. So we just sat there, thinking up small talk while he stood, hugging the kidney bucket, grinning, licking his lips.

THERAPY

You took me to the park. You got me there, I think, by promising we’d visit the ice cream van, but when we got there you took me by the hand and dragged me across the grass. I fell a few times, bruising, skinning, because I wore shorts that day. You shouted at me to hurry up, insulted my cultural heritage in no uncertain terms, brought my mother into it. There were fifteen people standing in a circle, I suppose waiting for us. Everyone in the circle started laughing, out of nothing, out of nowhere. They looked at me and laughed. You laughed most, but I hit the man to the other side of me, because he looked like he could take it.

DOCTOR

I went to see a doctor, finally. Suburban doctor, the kind with a normal house as their surgery, the sort of house you’d drive right past if it didn’t have a wheelchair ramp layering up to the front door. The reception was where you’d think a lounge room might be, normally, and the receptionist had her desk next to a nice lamp, where you’d maybe put an armchair to read a book in. The doctor came out and she was dressed casually, the way someone might around their own house. She took me into her surgery, which would normally be a bedroom, and it had a clear view out onto a tidy garden. A row of pots, with herbs, sat along the windowsill. She sat me down and I looked up at the ghost of a suburban ceiling, imagining remnants of glow-in-the-dark stars.

ACOUSTIC

While she was still in the studio, I crept out to the verandah to have a coffee and a cigarette. It had been raining all week; everything I touched held damp like a memory. I looked out at the big bruise of the sky. The thing still awed me, really: all that space. I was only used to my small section of the universe, hemmed in by all the awkward augers of civilisation. Out here, though, other worlds still seemed possible. I could hear muffled piano. My mind filled in the rest of the song, her voice filling out the chorus. I blew smoke up into the dying day, leaving my breath to travel where it would.

BAND

My friends and I decided to start a boy band. One of us bought three books on the subject, but they all turned out to say pretty much the same thing. One of us bought headbands, but they were all the same colour, and we were fairly sure that wasn’t right. I brought along my electronic drum kit, still in the box, but when no one could find a way to plug it in, we realised it was actually a picnic set. My best friend, however, came through with the goods. He had contacts high up in the music industry, and had already organised us a manager. The manager was into what he called Real Raw Talent, which, as it turned out, meant our penises, which he insisted on seeing before he could score us that huge gig at Central Park in New York, which was going to be pretty sweet.

FANTAISIE

Walking through a shopping centre, an old-fashioned one, with a woman who rode the lifts with you and pressed the buttons. A grand piano in the foyer, an elegant, arched man in coattails playing nocturnes and waltzes. We spent the day riding the escalators, craning our necks to watch the thin strings inside the piano tremble as the hands of the coattail man swept across the keys, those hands, those fingers, and his feet on the pedals, dampening, accentuating. Eventually a security guard approached us, tapped his watch, but left us to listen to the last song.

EXCHANGE

The guy was some expert in old coins. At least this was what the sign on his stall said. Something-ologist, something-apidrist. His fingers had hair all the way up them, sprouting from knuckles and wrinkles. He shot me with a crooked grin, clucked at a schoolgirl pawing through a bucket of pennies. The guy beckoned me over, pulled out a velvet-covered box from inside his jacket. He shooed away the schoolgirl, drew me in with his free hand. I shuffle closer, and the guy opened the box. Oh, I said, peering inside. So not coins, then. I tried to back away, but his grip remained on my arm. Definitely not coins.

SOUTHERN

She came from Princess Ragnhild Coast. Just appeared one day, at my doorstep, shivering. Strange for someone who came from the cold. Her hair was flax, floating in corn wisps. I watched her body shaking, for a while, entranced that someone could move that much without trying to. Involuntary reaction, I thought. Doctor’s hammer to a knee. Pepper tickling out a sneeze. I took her in, bracing her tiny body. My skin above her coat of goosebumps. Which meant, so it went, that a stranger walked across her grave.

OUT

It was very nearly the end of the toothpaste. I meted out tiny bits on the end of my brush: first child-sized blobs of white, and then dots, then flecks, and then nothing. I checked the news wires that night—as we all did, I suppose—but there was still no good news. The next morning, the street was littered with the jags of broken plastic, scattered bristles.

COMPARE

We’d been seeing each other for over three months, and we were circling. Trying to decide if what we had was worth continuing. Whether this person’s face was the one we’d want to watch change, whether this person’s shoulder was the one we wanted touching ours every night as we slept. How tall are you, you asked me, in centimetres? Which way do you vote, I asked you, really, when you get into the booth? Could you love a sick child? Can you hold a note? Which films did you cry in? How much do you read? Health issues? Medications? Perversions? We stayed up all night, coring out each other’s personalities, digging for truths we’d never actually need to know until a time when it wouldn’t matter anyway. We fell asleep, together, shoulders touching, bodies rising to fall.

ASSISTANCE

We had an uncle, growing up, who would never do anything for himself. I say an uncle, but he looked nothing like the rest of us, and I couldn’t find him in any of our photo albums. We’d drive over to his house nearly every day, with a sausage casserole or baked eggs—something he could eat for three meals—and then we’d ferry him around on various errands, buying him stamps or the newspaper or maybe a Danish pastry, returning his overdue videos and library books. And it wasn’t as if he was in a wheelchair or blind or anything; he always ran down the driveway to meet us, sometimes executing a little twirl. When I’d ask mum why we did so much for this man, she’d tell me to shush down, and that my uncle’s toenails weren’t going to buff themselves.

STAT

She wanted me to take the bird to the vet, but I knew the little bastard was faking it. Coughing behind his wing, shaking his legs when he knew we were looking. It was all the medical dramas she watched, I was sure of it. The bird sitting in the room with her while she watched chisel-jawed actors solve a procession of rare and exotic prime-time diseases. Gave it too many ideas. One night I stayed up late, casually holding our mini-camcorder in my pocket. Wanted to catch it jumping around the cage, doing cartwheels around its perch. But it was too crafty. Just sat there, making pathetic squawks. The next morning we woke to find half its feathers gone. She screamed, picked up the cage and shoved it into my arms. Deal with it, she said to me, we haven’t got much time. When I started to talk, she said, Damn the consequences, just get it done! There’s a life at stake, dammit! Then she looked off into the distance, waiting, I guessed, for an ad break. Then the bird made a noise like a heart monitor. Cheep. Cheep. Cheeeeeeeep.

RADAR

I guess they usually caught these things early, but this time it was obviously too late. The captain came over the loudspeaker and told us, in cool, mathematical terms, that we would probably end up in the side of a mountain. He didn’t tell us when this would happen, strangely, only that it would. This confused most of us on board. One of us screamed, another laughed. What if he means twenty years from now? said the man next to me. What if he means we’ll end up in the side of a mountain in, like, fifty years—or seventy? I nodded at the man. I certainly couldn’t fault his logic.

SHRAPNEL

You insisted our first date be held at a certain time of the year. Moon cycles, tides rising and falling—everything had to be perfect. You had that face—that body—so I let you make me wait. You wouldn’t talk to me until you’d done your calculations, boiling up herbs and strange powders with animals on the labels you made me buy from corner shops in dangerous neighbourhoods. I caught a bullet one night coming out of a back room apothecary. I was told later, by a duty nurse, that I’d worn the wrong coloured trousers. I called you from the hospital, asked you if all this fuss was really necessary. And then you said, For you it is, yes, and suddenly the pain in my left buttock where the bullet had entered went away, as if by magic.

RECORD

She had maps spread out all over the floor. I told her they looked blank, but she told me, in all seriousness, that they were charts of salt flats. While I brewed some tea, she pushed tiny matchbox cars across the paper, making motor noises with her mouth. I asked her how fast she was intending to go, and she told me that she aimed for near the speed of light. I chuckled at her then, but afterwards, when she showed me the pictures, I think even a scientist would have been impressed.

SHOWER

My dad told me once never to drink the water from the shower. I wanted to know even if I was thirsty could I do it but he said no, not under any circumstances. I pestered him about it for a while, wanting him to tell me what made shower water so different from water that came from the tap, but he gave me the silent treatment. Every time I took a shower, back then, I’d look up at the water, blinking away the steady streams, wondering.

SPORTS

We saw each other—as was the cliché—across a crowded room. A celebration for some sporting team we both happened to stumble into. Each of us trying to find our way home, taking a shortcut through the hotel lobby, running straight into a wall of red and white. Somebody grabbed my shoulder and tried to see above the crowd. Someone fell backwards into you, spilling warm beer down your leg. We both moved away, tried to find some room in the crowd, caught each other’s eye. Both thought that maybe the other was here for the sports team, and that would be a pity. Tried to communicate with hand gestures and facial expressions. Are you—is this—does it? And both of us, nodding, yes, let’s get out of here, together.

Thursday, May 28, 2009

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

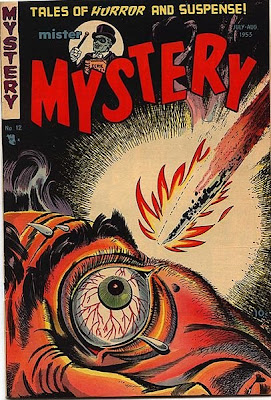

MISTER MYSTERY

Sorry there haven't been many posts of late, but I've been feverishly working to create something special to celebrate my appearance at the Emerging Writers Festival this weekend. Alls I can say for now is it will begin at 12.00am on Saturday morning. Or midnight Friday, if you prefer. Stay tuned...

Thursday, May 21, 2009

MYSTERIFFIC REVEALED

So now it's official. The book UNTITLED by UNKNOWN (as previously discussed) has been revealed to be...

The Link by Colin Tudge

What is "The Link"? A 47 million year-old lemur-like creature with opposable thumbs and ... a tail! That is to say, a possible missing link, complete with semi-preserved fur and everything! Now while I calm my inner science nerd, head over to the official site to find out about the book, the film, the T-shirts and the themed amusement park. David Attenborough's inolved, so you know it's going to be good.

The question remains, why did Hachette decide to make bookshops pre-order the book not knowing anything about it? I personally would have ordered a lot more copies if the information was revealed to me yesterday, when the news broke via a New York press conference.

Anyhoo, I'm off to dig up the back yard. Just in case.

The Link by Colin Tudge

What is "The Link"? A 47 million year-old lemur-like creature with opposable thumbs and ... a tail! That is to say, a possible missing link, complete with semi-preserved fur and everything! Now while I calm my inner science nerd, head over to the official site to find out about the book, the film, the T-shirts and the themed amusement park. David Attenborough's inolved, so you know it's going to be good.

The question remains, why did Hachette decide to make bookshops pre-order the book not knowing anything about it? I personally would have ordered a lot more copies if the information was revealed to me yesterday, when the news broke via a New York press conference.

Anyhoo, I'm off to dig up the back yard. Just in case.

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

NEWRAKAMI GETS SLIGHTLY CLOSER

There's nothing quite like the anticipation of a book you already know will be insanely great. The Millions has a nice take on Haruki Murakami's much-anticipated and secrecy-shrouded monster novel "19Q4". Read about it here . No date on English translation yet, but it's still exciting!

Monday, May 18, 2009

GRANDMA'S CHEST, IDENTITY THEFT

I promised myself I wouldn't, but I am such a sucker for dubious book covers. I recently caught up with a rep from Boolarong Press, a commercial/joint venture/vanity press mainly servicing south-east Queensland authors, and was impressed by their commitment to local stories, and serving up useful and timely books, such as this one. That said, their catalogue contained some all-time favourites such as this:

In other news, Techcrunch gives us yet another reason Amazon is evil. Turns out it's easy to steal the identities of popular blogs (and even books!) and publish them to the Kindle, reaping the profits. Find our more here.

If you need calming down after that disturbing news—and at the risk of straying from my chosen field of creative endeavour—Iron and Wine is celebrating the imminent release of a 2-disc collection of rare and out of print tracks, Around The Well, with a free download of alternate tracks from 2007's brilliant The Shepherd's Dog. Click this link to start downloading, and feel those Amazon-related copyright worries float away.

If you need calming down after that disturbing news—and at the risk of straying from my chosen field of creative endeavour—Iron and Wine is celebrating the imminent release of a 2-disc collection of rare and out of print tracks, Around The Well, with a free download of alternate tracks from 2007's brilliant The Shepherd's Dog. Click this link to start downloading, and feel those Amazon-related copyright worries float away.

FURIOUS HORSES HITS MELBOURNE!

For all those (three) Furious Horses fans in Melbourne, I will be down your neck of the woods soon for the Emerging Writers Festival, whose organisers have very kindly invited me down to talk about this blog, in a session called From Here to There, at the Melbourne Town Hall on Saturday May 30th at 12.30pm. Now I don't want to alarm you, but it'll just be me up there for one hour, in conversation with Beth Proudley, somehow coming up with interesting things to say about the process of starting Furious Horses, how I developed it, and where it's gone since -- that is to say, please come armed with some questions, because this is all I have so far:

1. Inaudible mumbling in response to chair's questions (2 mins)

2. Brief ventriloquism act featuring Stabby, the rambunctious black pen (13 mins)

3. Maurie Fields impression (4 mins)

4. Awkward silence (15 mins)

4. Short reading from my unpublished collection of genital health poetry (2 mins)

5. Miscellaneous shouting (8 mins)

Which still leaves 16 minutes to fill. Your suggestions are welcome.

Anyway, if you'd like to book a ticket to the day's entertainment at the Town Hall (featuring the talents of creative types far cleverer and more talented than I), or any other session at the festival, please head over to Greentix and make your booking. I am told with good authority that if you book a weekend ticket, you will get a showbag! The festival runs from Thursday May 23 through to Sunday May 31. I'll be there for the last few days, so if you see me, make yourself known with the Secret Furious Horses Handshake, or SFHH*.

So I hope to see you in Melbourne, The City of ... String.

Chris

* For instructions on how to properly execute a SFHH, please read this.

1. Inaudible mumbling in response to chair's questions (2 mins)

2. Brief ventriloquism act featuring Stabby, the rambunctious black pen (13 mins)

3. Maurie Fields impression (4 mins)

4. Awkward silence (15 mins)

4. Short reading from my unpublished collection of genital health poetry (2 mins)

5. Miscellaneous shouting (8 mins)

Which still leaves 16 minutes to fill. Your suggestions are welcome.

Anyway, if you'd like to book a ticket to the day's entertainment at the Town Hall (featuring the talents of creative types far cleverer and more talented than I), or any other session at the festival, please head over to Greentix and make your booking. I am told with good authority that if you book a weekend ticket, you will get a showbag! The festival runs from Thursday May 23 through to Sunday May 31. I'll be there for the last few days, so if you see me, make yourself known with the Secret Furious Horses Handshake, or SFHH*.

So I hope to see you in Melbourne, The City of ... String.

Chris

* For instructions on how to properly execute a SFHH, please read this.

Friday, May 15, 2009

YSTERIFFICMAY

Just looking at the recent keyword searches that led people to this site, it's clear that more than a few inquisitive minds have been trying to figure out the identity of the mysterious book released by Hachette on May 28 called UNTITLED by UNKNOWN (as previewed in my previous post). Well, friends, I can save you the trouble, as I've tried every possible Google search term to find it and have come up short.

As for the other title I previewed, Simon and Schuster's Untitled on China, well, things get a little easier. The details of the book were inadvertently revealed to booksellers a few weeks ago, when online buying group Leading Edge published the details of the book on their site (available only to booksellers). We were urged to keep the identity of the book a secret, and that is something I shall uphold. That said, Isonerpray of the Atestay by Haozay Iyangzay should make for very interesting reading (I think impenetrable codes are allowed...).

And for those who can't read Pig Latin—or who don't want to lest they contract a rare strain of grammerian flu—you can always visit Simon and Schuster's American site, where the details of the book are available in full.

As for the other title I previewed, Simon and Schuster's Untitled on China, well, things get a little easier. The details of the book were inadvertently revealed to booksellers a few weeks ago, when online buying group Leading Edge published the details of the book on their site (available only to booksellers). We were urged to keep the identity of the book a secret, and that is something I shall uphold. That said, Isonerpray of the Atestay by Haozay Iyangzay should make for very interesting reading (I think impenetrable codes are allowed...).

And for those who can't read Pig Latin—or who don't want to lest they contract a rare strain of grammerian flu—you can always visit Simon and Schuster's American site, where the details of the book are available in full.

Thursday, May 14, 2009

HIPSTERS UNITE (AND COLOUR IN)!

This has to be quick because I'm busy listening to the new Wilco album, but in the spirit of music and books colliding, this is worth a look:

Artist Andy J Miller and Canadian nonprofit The Yellow Bird Project have created this awesome collection of mazes, dot-the-dots and colouring pages based on bands like The National, Rilo Kiley, The Shins and Devendra Banhart. All royalties from The Indie Rock Colouring book go to charity, so get pull on those black stovepipes and tight cardigans and get down to your nearest indie bookshop to pick one up. Don't worry though, it's not out till September, so you'll have time to get your hair right.

Thursday, May 7, 2009

IMPORTANT ARTIFACTS

One of the most exciting parts of my day at the bookshop I work at is pouncing on a fresh delivery from our American book supplier. And while the box may be filled mostly with customer orders pertaining to urine therapy or which particular race of alien begat the universe, it also contains the books that I order in because I think they're cool, and I think no other bookstore will have.

One of these arrived today, Leanne Shapton's Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry. What the book is, essentially, is a fictional auction catalogue of one couple's possessions and artifacts, which charts, through inanimate objects, the dissolution of the couple's relationship, from loving start to bitter end. It truly is an original, and well worth checking out.

You can read more about it here, watch a short video with Leanne Shapton here, and you can buy the book, of course, here.

One of these arrived today, Leanne Shapton's Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry. What the book is, essentially, is a fictional auction catalogue of one couple's possessions and artifacts, which charts, through inanimate objects, the dissolution of the couple's relationship, from loving start to bitter end. It truly is an original, and well worth checking out.

You can read more about it here, watch a short video with Leanne Shapton here, and you can buy the book, of course, here.

Wednesday, May 6, 2009

DICKENSIAN

In what is becoming rapidly a truncated, shortcut world, it's a pleasure to see someone making URLs longer and more enjoyable, rather than trimming them down, tinyurl-style. Over at dickensurl.com, you can turn that boring weblink into a piece of art. For instance, www.furioushorses.com becomes:

http://dickensurl.com/9b9e/Mrs_Varden_was_a_lady_of_what_is_commonly_

called_an_uncertain_temper__a_phrase_which_being_interpreted_signifies_a_

temper_tolerably_certain_to_make_everybody_more_or_less_uncomfortable

Pure genius.

http://dickensurl.com/9b9e/Mrs_Varden_was_a_lady_of_what_is_commonly_

called_an_uncertain_temper__a_phrase_which_being_interpreted_signifies_a_

temper_tolerably_certain_to_make_everybody_more_or_less_uncomfortable

Pure genius.

Tuesday, May 5, 2009

WHAT THE WHAT?

It's only May, but I already feel that I've seen my favourite title of the year so far. My good friends at Gary Allen, laudably Australia's largest home-owned book distributor and publisher (but also agent for some very dodgy esoteric and shouldn't-have-been-published titles) are bringing into the world in July this mind-boggling thing:

Like Chocolate for Women?! Now I enjoy wordplay as much as the next person, but this book's title has me perplexed. Is it trying to be "Like Water for Chocolate"? And what indeed is this relationship between women and chocolate? And how does it apply to getting back on top (of whatever it is you want to get on top of) and in control of your life? Only time will tell.

And while we're looking at Gary Allen's July highlights, why not experience the ocean with the innocent delights of The Rainbow Fish, and his new friend Creepy Octupus. Do fishes have a "swimsuit area"? And notice I didn't even mention the author's last name. Because I'm not crass like that.

And while we're looking at Gary Allen's July highlights, why not experience the ocean with the innocent delights of The Rainbow Fish, and his new friend Creepy Octupus. Do fishes have a "swimsuit area"? And notice I didn't even mention the author's last name. Because I'm not crass like that.

But Gary Allen shouldn't really worry. Their homepage reminds us that they have the distribution rights to probably the two biggest nonfiction moneyspinners in Australian publishing. Fair play to them.

Friday, May 1, 2009

MYSTERIFFIC!

Sometimes publishers use the tactic of urgency to get them to buy their books. Sometimes they use the power of secrecy, and sometimes they use the bargaining chip of importance. My new favourite is being bandied about by Hachette Australia. Here is an excerpt from their ambitious sell-in sheet for UNTITLED by UNKNOWN, strictly embargoed until its release on May 28:

"Lying inside a high security vault, deep within the heart of one of the world’s leading museums, is an extraordinary specimen that could be the most important scientific discovery of recent times. Fewer than a dozen experts know of its existence; its value to the world is inestimable. This is a discovery that will change textbooks, change science, and change how we understand the human race.

The author of UNTITLED has been given exclusive access to all of the research and the team of

top scientists who have been validating the discovery, the announcement of which will send

shock waves around the world."

Yes, well. This tactic is more often reserved for biographies, such as Simon and Schuster's Untitled on China, or, a few years ago, this little pearler, which you did not get on its release date unless you ordered quantities in boxes. Anyway, expect to be blown away by UNKNOWN's riveting story of UNTITLED, providing Hachette's team of top scientists can keep a lid on the inestimable shockwaves that will reverberate around the world. Honestly, who would get sucked in by this guff?

I ordered 6.

N.B. Hachette's truly excitable marketing team also came up with one of my favourite spriuks ever, when describing this cover. It is, according to the press release: "Packaged beautifully with cult object production values that will make this object as cult as the ipod."

Cult as, bro!

"Lying inside a high security vault, deep within the heart of one of the world’s leading museums, is an extraordinary specimen that could be the most important scientific discovery of recent times. Fewer than a dozen experts know of its existence; its value to the world is inestimable. This is a discovery that will change textbooks, change science, and change how we understand the human race.

The author of UNTITLED has been given exclusive access to all of the research and the team of

top scientists who have been validating the discovery, the announcement of which will send

shock waves around the world."

Yes, well. This tactic is more often reserved for biographies, such as Simon and Schuster's Untitled on China, or, a few years ago, this little pearler, which you did not get on its release date unless you ordered quantities in boxes. Anyway, expect to be blown away by UNKNOWN's riveting story of UNTITLED, providing Hachette's team of top scientists can keep a lid on the inestimable shockwaves that will reverberate around the world. Honestly, who would get sucked in by this guff?

I ordered 6.

N.B. Hachette's truly excitable marketing team also came up with one of my favourite spriuks ever, when describing this cover. It is, according to the press release: "Packaged beautifully with cult object production values that will make this object as cult as the ipod."

Cult as, bro!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)